Sermon of Bishop Bernard Fellay for the Funeral of Bishop Huonder

Bishop Bernard Fellay presiding over the funeral of Bishop Vitus Huonder

On Wednesday, April 17, 2024, during the funeral Mass of Bishop Vitus Huonder in Écône, Bishop Bernard Fellay, the former Superior General of the Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX), preached the sermon, first in French, then in German. The oral character of the sermon has been retained in the following translation.

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.

Your Excellencies,

Dear colleagues in the episcopate,

Dear Superior General,

Dear colleagues in the priesthood,

Dear Sisters,

Dear faithful,

We are gathered here near the mortal remains of His Excellency, Bishop Vitus Huonder, to pay him our last respects, to conduct him to his final resting place.

We also wish to accompany him with our prayers, for, through the Church, we know that after death there is judgment--post mortem stat judicium. We also know that, for those in positions of authority, the judgment is more serious, because of their greater responsibility. The bishop answers in a more severe manner than the faithful; it is Holy Scripture which tells us this. The bishop answers for all the souls of his diocese.

The Lord is just, and the time of mercy is on this earth. After, we find ourselves before the just Judge. And the Church, while entrusting herself to this mercy of the good God who died to save us, knows how important it is to accompany the dead through prayer, imploring the good God for eternal rest--requiem æternam dona ei Domine--grant them, grant him this rest, this eternal rest, and may the light--lux perpetua--this perpetual light shine upon him.

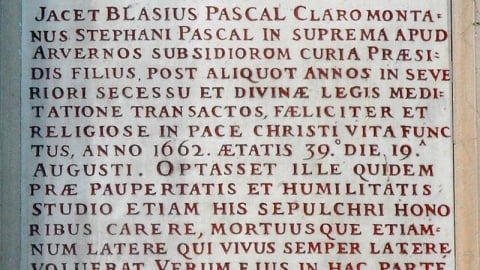

Bishop Huonder's tomb

The Path to the Society

Of Bishop Huonder, who was with us these last years, we remember his affability, his serenity. He radiated it, this kindness. He was a benevolent bishop. We did not see in him a spirit of criticism, a spirit of revenge. There was none of all that. He wanted to be someone who built bridges. In fact, that’s what the word Pontifex means: It is someone who builds bridges.

And at the end of his life, there was this request, this wish, the last request, as they say: “I want to be buried in Écône.” This is a decision at which, certainly, we rejoice, but which shocks more than one person. But it seems to me that today, it is important that we try to understand his decision. To do this, we must look a little at history, and also a little at the history of the Society. I think it is no secret that our Society of Saint Pius X is perceived as a sign of contradiction. I even used this expression when explaining it to the Holy Father: it is a reality, and a reality which contains a mystery.

We have had discussions with Rome. At at one point--already under Pope Francis, at the beginning--Rome asked some bishops to enter into contact with us for discussions. There were four of them. There were an auxiliary bishop, a bishop, an archbishop, and a cardinal. But we met each one separately. Each came into our houses--for the most part, into our seminaries. And there, in a closer and perhaps more human contact, they came to know us perhaps better than simply through theological exchanges.

And it was after these exchanges that Bishop Huonder knew us better--discovered, perhaps, what is hidden under the sign of contradiction. So much so that, when he was going to retire from the diocese, he asked to be able to stay with us. He spoke of it to Rome, he spoke of it to Pope Francis, who, at the time, did not pose any objection, did not say much. Better, from the mouth of Bishop Huonder himself, we know that one day the Pope had said to a priest: “What he is doing there is good.” And he received explicit approval from Ecclesia Dei.

In fact, through seeing us, it was obvious to him that we are not schismatic. During my first audience with Pope Francis, he told me: “You are Catholic, I do not condemn you.” We see from this that there are--one could say--various levels of understanding things.

The Treasures of Tradition

And at the Wangs school, for four years, Bishop Huonder went to study, examine, go into depth with the writings of Archbishop Lefebvre, what the Society says. He saw it live, he saw what we are doing. He undoubtedly discovered the “why” of the sign of contradiction. We touch there a mystery. And it is a mystery which goes beyond--one could say--the Society. Already, Pope Benedict XVI said: “You represent much more than what you are.”

It is a great mystery, first of all, to see that it is not us who seek to be a sign of contradiction, but that it is indeed a reality, a provision of divine Providence. Just as it is a provision of divine Providence to have as concentrated in the Society a set of treasures, which are the treasure of the Church, and which, in part, have been put aside, forgotten, neglected. It is as if the good God had wanted to concentrate his treasures in this small fraternity. It is a great mystery of our time. We are not alone, but it is quite impressive to see how these goods--which, again, are the goods of the Church, which are not ours alone--are summarized by this term, “Tradition.” St. Pius X already said: “The Church is Tradition.” The Church cannot separate herself from her Tradition. It is not possible. It is her being.

Tradere: when we speak of Tradition, we say that we have received... it is God Who has deposited, Who has entrusted these treasures to the Church. The Church lives in this. It is her life. She cannot be separated from it; that would be death. When we say that the Church is a society, we must say that she is essentially supernatural. It will never be through human means that the Church will be able to live. What keeps the Church alive are the means which are truly divine, which come from God. It is the life of God, it is the life of grace, which is given to us by the Faith, by the sacraments.

And all these treasures--Bishop Huonder saw them, he enjoyed them, he shared them with us. Because he found them with us. He rediscovered the religion of his childhood. Separating from the Church is out of the question. No! We are of the Church. Bishop Huonder was happy. He carried with us this sign of contradiction. Naturally, not everyone rejoiced to see him with us. Regardless, he carried this sign with us.

Bishop Huonder at the Corpus Christi Procession in Jaidhof, Austria

Suffering for the Church

And that is when he said: I want to be buried here, close to the bishop who suffered so much for the Church. We could say: “But you are abandoning your diocese!” This must not be pondered in too human a way. Let us try to imagine Bishop Huonder facing his death, facing his imminent departure from this life. He knew it: that soon he would appear before the Savior, before the Lord God. He would have to render an account of his life. These last days are thus incredibly important. They are decisive for all eternity. It is serious! We do not make such decisions lightly: I want to be buried there. We asked him: in the diocese? No: over there! It was his decision. It surprised us. Of course, it is with joy than we want to make this happen, but we also want to understand this desire. What did he really want to express by this? I repeat: the last act of our life here on earth determines our eternity. If one is sufficiently conscious of this, then he wants this act be the greatest, the best, the most perfect. Who would be crazy enough, at that moment, to fix upon an act contrary and opposed to the good God? That final moment is the moment to fix upon the holiest act, the act which renders the most love possible, which glorifies the good God more, and assures us salvation.

Christ Wanted to Die Outside of Jerusalem

There is something very mysterious that I would like to associate with this thought. It must be taken in a completely mystical way, not too literally. Our Lord wanted to die outside the walls of Jerusalem. And here we have a sort of reproduction: Bishop Huonder dies, or is buried, outside, one could say, the walls of his diocese. As I said, it must not be taken literally, because, in this death of Our Lord, who would ever dare to say that Our Lord at that moment abandoned Jerusalem? No, He did not abandon Jerusalem; but He is the center, and the center of the world. He draws everything to Himself. He does not limit salvation to Jerusalem. This death outside the walls is like the character of the Catholic Church: it is universal. Jesus died for everyone. First of all for the Jews, as Holy Scripture says, as St. Paul says so often: first the Jews, then the Gentiles. This is not a rejection.

Salvation Comes from the Cross

It would therefore be completely erroneous to take this act of Bishop Huonder as a rejection. It is not at all that. But it is a mystery! And this mystery, I do not know if he discovered it or if he found an affinity for it, something that he already knew, because it is so Catholic... it is the reality of the Cross. Salvation comes from the Cross.

If the good God allows us to be a sign of contradiction, is is not for the sake of contradiction. This is because Our Lord Himself, according to the prophecy of Simeon, is this sign of contradiction. He who brings peace to men of good will became a sign of contradiction. And whoever wants to live with Our Lord--this is a word of the Gospel--whoever wants to live piously for Our Lord will suffer persecution. If we want to live with Our Lord, somewhere we will have to suffer for that. That is how it is! This invitation to embrace the cross, we see it many times in the Gospel: “If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross daily, and follow me” (Lk. 9:23). “And he that taketh not up his cross, and followeth me, is not worthy of me” (Mt. 10:38). Holy Scripture also says: “For unto this are you called: because Christ also suffered for us, leaving you an example that you should follow his steps” (I Pet. 2:21). That is what it means to embrace the Cross. It is a mystery.

It has been like this since the beginning, and it is for this that the Church on earth, since the beginning, has been called the Church Militant. The Church will always have to suffer from hatred: “the world hateth you” (Jn. 15:19). And Our Lord presented this as something absolutely normal. “The servant is not greater than his master. If they have persecuted me, they will also persecute you” (Jn. 15:20). And this cross, this suffering, it is what God chose in order to satisfy, to make up for sin, to save us.

And, once again, I think that Bishop Huonder must have seen this mysterious reality with us; this grace which rests in us is this union deep within the church, because the whole life of the Church comes from the Cross. All the salvation of the Church, all the grace which gives life to the Church, comes from the Cross. Archbishop Lefebvre had this grace to grasp this reality and transmit it to us, and I think that this is what Bishop Huonder saw here. This is not said from the rooftops.

What we often see of the Society is the ancient Roman Rite. In fact, these things are essential just as the vase that contains water is essential: a vase is needed to hold water. This spirit, the Christian spirit, needs a vessel. And we see it, the experience of the Church, these 2,000 years of the Church, show us that these rites, ancient, venerated, polished by the Holy Ghost, contain the Christian spirit. And this act, “I want to be buried here, close to the bishop who suffered so much,” is like saying: I want to embrace this Cross. This choice is not for the Society alone. It is much more profound, much more profound. It is the spirit of Our Lord.

We want the resurrection, we all want it, we want our dear Bishop Huonder to rest in peace. And I truly believe that he set a sign for this, a sign for all.

This sign that he places before history, which calls out--well, really, let us beg that it helps us all to better understand and to truly embrace this spirit of Our Lord Jesus Christ, Who completely, absolutely entrusted Himself to his Father on the Cross, for the greater glory of the Father, for the salvation of men.

Amen.